An hour before the panel of authors was set to take the stage, the line at the 2019 Portland Book Festival event was already at least 1,000 hard-core, book-clutching fans deep, most of them craning their necks and standing on tiptoe, trying to game out whether they were close enough to the front of the line to snag a spot inside the 376-seat Whitsell Auditorium in the Portland Art Museum’s basement.

Clearly, festival organizers had underestimated the intense enthusiasm for the featured authors—not pop sociologist Malcolm Gladwell or former United Nations ambassador Susan Rice, who were the festival’s nominal headliners—but instead a group of middle- grade graphic novelists, among them one of the format’s biggest rock stars, Bay Area author-illustrator Raina Telgemeier, whose 2010 debut memoir, Smile, kicked off a craze that shows no signs of abating.

Even as the publishing industry overall jockeys to compete for consumer eyeballs and societal relevance within an ever-expanding digital landscape and a news cycle that just won’t quit, this particular niche—graphic novels for kids ages 7 to 12 or so—has exploded. The category, which barely existed at the turn of the century, continues to expand both in sales and subject matter.

And Portland, with its long legacy as a comics industry nexus, has emerged as a key incubator for many of the tastemakers who are fueling the graphic novel gold rush.

“Portland has an enormous amount of cartooning talent, period,” says writer and illustrator Barry Deutsch, who has worked in the city for decades. “There are two or three centers—Brooklyn, Chicago, and Portland. It’s sort of like how the QWERTY keyboard became dominant. It’s not that Portland is superior; it’s that there happened to be a lot of cartoonists, who encouraged more. Now, people are switching to middle grade and young adult, because that’s the growth market.”

Let’s back up a little. In the ’70s and ’80s, comics-loving kids had the Sunday funnies in the newspaper, the -Man collective (Spider, Super, Bat), and the anodyne Archie Andrews and his gaggle of Pals N’ Gals, forever congregating at Pop Tate’s Chock’lit Shoppe. Comic books were stapled affairs, not square bound books, and not especially subversive, as per the rules of the 1950s era “Comics Code Authority.” For the non-comics-historians out there, comic book publishers agreed to abide by the code to avoid government censorship; the code, which existed until about the turn of the century, mandated the triumph of good over evil and put the kibosh on scenes of “depravity, lust, sadism, masochism,” among other taboos.

From the late 1980s through the early 2000s, when many of today’s creators were themselves middle-grade readers, things were getting weird. The underground zine scene and small presses—like Portland’s influential Oni Press—were flowering; The Simpsons and Daria stormed TV, and girls were hitting their stride as fleshed-out main characters in works like the Latinx-inflected Love and Rockets and the autobiographical feminism of Lynda Barry’s Cruddy. (Barry was a contemporary of Portland-born Simpsons creator Matt Groening at the Evergreen State College in Olympia.) Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, a memoir of growing up in Iran during the Islamic Revolution, started showing up on post-9/11 school reading lists; a movie version followed in 2007.

And then there were manga, the wildly popular Japanese comics widely translated into English in the 1990s, featuring slice-of-life, girl- and teen-centric stories worlds removed from the swashbuckling, macho superheroes who ruled the comic book shop.

“Borders and Barnes and Noble started a dedicated manga section,” says Gina Gagliano, a Reed College alumna who is now the publishing director of Random House Graphic. “Looking at that, what is the counterpart of manga as something we can generate in the US instead of bringing over translation? The answer (was) graphic novels, especially graphic novels for kids and teens.”

A truly new category in publishing is extremely rare. But in 2005, when Scholastic—not one of New York City’s Big 5 publishing houses, and best known for its annual school book fairs—published a full-color compilation of cartoonist Jeff Smith’s fairy tale–inspired Bone: Out from Boneville—it was honestly different, a bridge between picture books, comics, and traditional fiction, perfectly positioned for a generation of kids who’ve grown up bombarded by images on screen.

Scholastic’s gamble paid off handsomely. In 2003, the comics market took in an estimated $66 million annually in retail sales; by 2019, that had topped $226 million, according to data from Nielsen BookScan analyzed by comicsbeat.com—and 18 of the top 20 sellers were graphic novels aimed at the tween set. Nearly all of the major New York publishing houses have since started graphic novel imprints; in 2019, in a nod to the format’s rising profile, the New York Times started a best-seller list devoted to graphic novels and manga. Telgemeier’s Guts, released in 2019, outsold every book in the country in its first week of publication, according to Publishers Weekly.

“In 2010, the same year I graduated from Lewis & Clark Graduate School of Education, that is the year that Smile came out,” recalls Aron Nels Steinke, a Portland elementary school teacher and creator of the cheerful, animal-populated Mr. Wolf’s Class series. Steinke now shares an editor at Scholastic with Telgemeier. “That is the book that she worked really hard to promote and get it out there, and it exploded the landscape. Publishers were like, ‘Oh, hey, we need to get some of this money.’”

Three West Coast authors have been particularly responsible for driving this growth. In addition to Telgemeier, whose modern coming-of-age tales rival Judy Blume in approachability, there’s Dav Pilkey, the Seattle-based author and illustrator behind the cheerfully daffy, fart-joke-sprinkled Captain Underpants and Dog Man series, dearly beloved of second graders everywhere. The third, American-born Chinese author Gene Luen Yang, who lives in San Jose, may be the most decorated of the bunch, as a winner of the MacArthur “genius grant” and a National Book Award finalist.

Their work and their success have inspired dozens of Portland’s writers and artists to create their own middle-grade graphic novels—and a surprising percentage of them have found notable success.

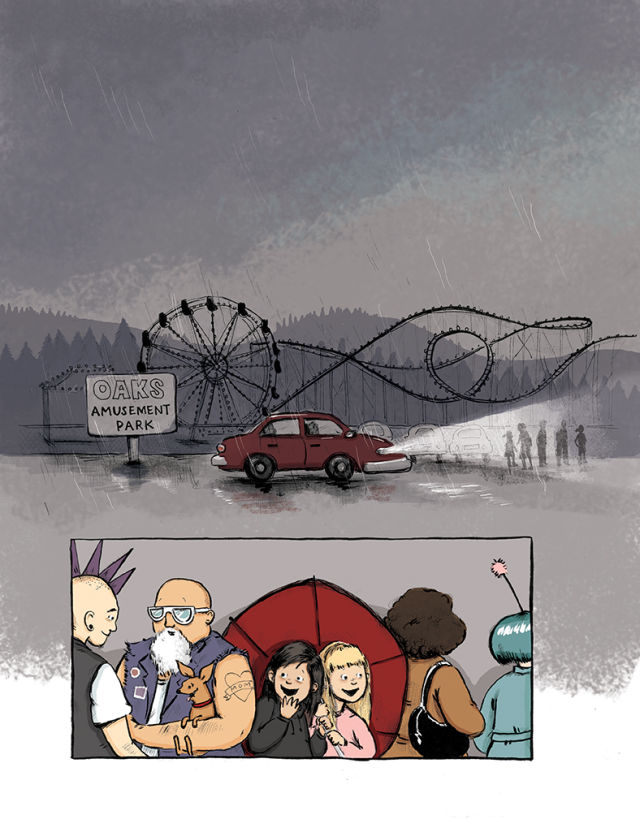

Take Victoria Jamieson, whose 2015 Roller Girl, published by Penguin Random House, is the most Portland-y book published for kids since Beverly Cleary’s Ramona series. The protagonist, Astrid, is growing away from her bestie, who is busy with ballet friends she’s made at a studio that’s a doppelganger for Sellwood’s Classical Ballet Academy. Plucky Astrid is more interested in spending the summer training as a junior roller derby player at Oaks Park, which is rendered in loving detail. The novel won the John Newbery Medal from the American Library Association, among the most prestigious awards in children’s literature; Jamieson (who has since moved back to her native Pennsylvania) was recently short-listed for the National Book Award for her latest collaboration, the graphic novel When Stars Are Scattered, depicting life in a Somali refugee camp through the eyes of a kid.

“Graphic novels are such an intimate reading experience. You come into someone’s house, look around, peek at their bedroom, see their kitchen. You are a part of their family, almost,” says Jamieson, who was first drawn to graphic novels by a Powell’s display. “Especially for kids in that middle range, you think you are all alone. [You wonder], do other people feel like I do? Do other kids feel this different than everyone else?”

The city was well-positioned to support a critical mass of graphic novelists, says Gagliano, who first got interested in comics while at Reed, when a librarian pointed her to the college’s archives of comics anthologies.

After all, Portland’s comics love affair runs deep. We’re home to Helioscope Studio, one of the country’s largest collectives of comic book artists, and two of the country’s seminal comic book publishers in Dark Horse and Image Comics, as well as Oni Press, an early independent pioneer in YA and adult graphic novels. We’ve also got a thriving comic books store scene (see a sampling on the previous page) that Gagliano says rivals New York City’s, and cross-pollination with animation studios Laika and ShadowMachine—all in all, a “good town for low-paying strange art forms,” says Vera Brosgol, who has hopscotched between work for Laika and her own graphic novels, including the wry Be Prepared, set at a Russian summer camp where borscht is often on the menu.

The cheap(er) rent that once drew artists to Portland is less in evidence these days, but the community is still a welcoming one. Prepandemic, creators would meet up for drink and draw nights at Crush on SE Morrison or mixers at Ford Food + Drink. The now-defunct Stumptown ComicCon was like a family reunion; the Portland Zine Symposium still draws crowds, even virtually, and the Independent Publishing Resource Center is a valued resource. This is a “big tent” kind of a crowd: When Gagliano last visited the city, before COVID shutdowns, she says she was given an internal spreadsheet of the city’s working cartoonists, “so they could make sure I didn’t miss anyone.” Breena Bard, a Portland resident whose first graphic novel, Trespassers, was published by Scholastic last spring, says it was Steinke who first encouraged her to enter the publisher’s “next great graphic novelist” competition. She won in 2017.

“I just keep thinking, it is the perfect time for me to be doing what I am doing,” Bard says, though the pandemic cut short her book tour. “I get to contribute to this huge body of work.”

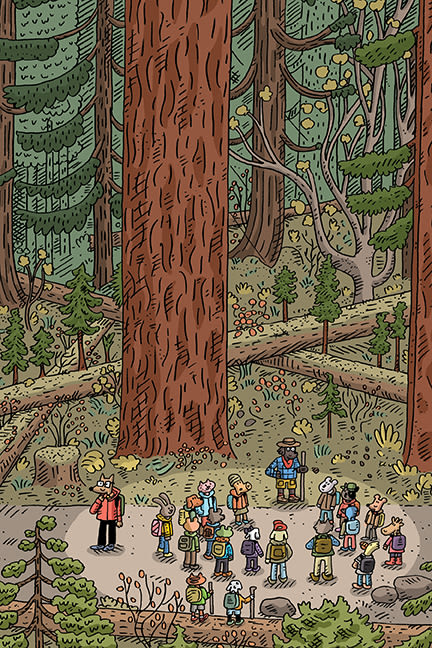

Vancouver, Washington, native Steinke is on the fourth installment of his Mr. Wolf’s Class series. He draws on his experience teaching fourth and fifth grades at Woodstock Elementary; in his latest, Field Trip, the namesake teacher (Steinke, in anthropomorphized wolf format) leads his class to a locale that looks an awful lot like Opal Creek’s Ancient Forest Center.

As the market has expanded, there’s been room for deviation from the autobiographical trail blazed by Telgemeier—Barry Deutsch, for example, was a struggling political cartoonist when he booked a table at a Stumptown ComicCon in the 2000s.

“Newspapers had less and less space that they were willing to use on cartooning,” Deutsch remembers. “I would get all these responses: we like your work, you’ve got lots of potential, there’s no way to make any money.”

So he created his Hereville series, which stars Mirka, an 11-year-old Orthodox Jewish girl who battles trolls (not the Internet kind, the fairy-tale kind). He brought samples to the two-day convention, and “by the end of Sunday, I had two publishers express interest, and an agent. [And I thought,] so, this is what it is like when you are not working in a dying field.”

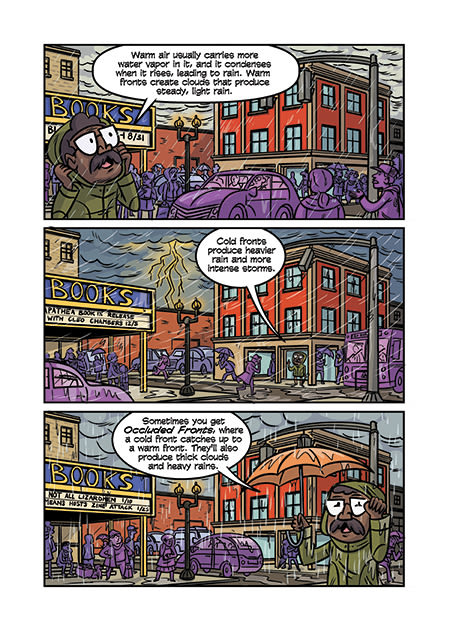

Deutsch has gone on to work on the graphic novelization of the incredibly popular Wings of Fire series, evidence that the science fiction/fantasy genre has found its way to the graphic novel format. So, too, have adaptations of classic literature, both faithful and less so—in the graphic novel version of Little Women, Jo March is the lesbian we all know she really was meant to be—and nonfiction books, like the Science Comics series on the weather produced by Portlanders MK Reed and Jonathan Hill.

“Having an educational aspect helps librarians justify putting comics into their collections, helps teachers justify putting them into the classroom,” Reed says. “If parents are reluctant, this erodes that. [Kids can say] ‘I am learning about molecules or something that I would not go look at in my free time.’”

Graphic novels do carry a stigma for some parents, says Katie Proctor, who runs Books With Pictures, a queer-friendly feminist comic shop in Southeast Portland. Customers will tell her that they’d prefer for their children to be reading “real books.”

And yet, when parents do cave and buy the books for their kids (or check them out of the library), they notice “there is a lot of rereading that happens,” Proctor says. “The ability of a third grader to just read the same book for weeks is really impressive. When you look at the mental work that happens when you are reading a comic, looking at the pictures, the background, the art style—there are so many different kinds of communication on the page.”

Jamieson, whose own son prefers picture books, seconds this: “When I write my books, I think very consciously about having the text say something totally different than the pictures, so the reader has to decide which is telling the truth. There might be a character looking really nervous and saying, ‘I am fine!’ It is a good way to navigate the world, judging what you are seeing as well as what you are hearing, and making truth of all that.”

When she opened, Proctor says she guessed that about a third of her sales would come from kids’ books; four and a half years later, it’s at least half.

Over the years, Proctor says she’s also seen a shift to more diversity among comics creators and the stories they are telling. Portland’s scene is not as diverse as it could be—Reed says she’s known plenty of those in the field who’ve moved here, stayed a year, and then left for less homogeneous pastures. But it does have its rising young stars, including Terry Blas, Sloane Leong, and more.

It makes sense that as the young readers’ graphic novel universe expands to meet demand, more creators are getting in the game, Bard says.

“I always consider myself an oddball, and I do think there is something about people finding a way to express themselves in comics who might not have had a voice otherwise, whether they are queer, trans, or writers of color,” she says. “Maybe because the medium itself is relatively new and still being formed, there is a place for people who haven’t found their space somewhere else.”

"middle" - Google News

December 13, 2020 at 08:00PM

https://ift.tt/2W7jFBL

Middle-grade Graphic Novels Are Storming the Bestseller Lists - Portland Monthly

"middle" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MY042F

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

No comments:

Post a Comment